At €520 per ton of CO₂ avoided, France’s hydrogen expenditures audit, Final Observations: Support for the Development of Decarbonized Hydrogen (translation by computer), reveals a stark economic reality, that decarbonized hydrogen produced via electrolysis remains stubbornly uneconomic, relying heavily on layers of public subsidies. This cost of abatement significantly exceeds the societal cost of CO₂ reductions typically pursued through other technologies. Such a price tag demands closer scrutiny, particularly when considering the scale and nature of the government support involved.

France’s ambitious national hydrogen strategy, outlined in the second iteration of its National Hydrogen Strategy (SNH2, released in April 2025), aims at rapidly scaling electrolytic hydrogen production to decarbonize key sectors. Over €9 billion has already been earmarked to accelerate hydrogen deployment, accompanied by significant political enthusiasm. However, this enthusiasm frequently overlooks fundamental economic considerations, as demonstrated clearly by the recent Cour des comptes report on the economics of electrolytic hydrogen.

The Cour des comptes is the French national Court of Auditors, responsible for auditing public finances and assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of government spending and policies. It is an independent judicial body that ensures transparency, accountability, and good governance in the management of public funds. It reports directly to Parliament and publishes evaluations, audits, and recommendations aimed at improving fiscal responsibility and public administration.

The figure of €520 per ton CO₂ reflects carefully considered assumptions about electrolyzer operation, electricity, and natural gas prices, all critical inputs for hydrogen production costs. Even under relatively optimistic scenarios, with more favorable energy prices, the report underscores that the economic burden of electrolytic hydrogen remains persistently high. Notably, the Criqui Commission previously estimated this cost at roughly €200 per ton CO₂, relying heavily on the coupling of electrolyzers with intermittent renewable energy and consistently low electricity prices.

The headline figure of €9 billion in public subsidies for hydrogen development significantly understates the true financial burden, as it excludes numerous indirect and hidden costs. Crucially, infrastructure investments required to build out extensive hydrogen pipelines, storage facilities, and dedicated distribution systems have yet to be fully accounted for in official estimates. Similarly, substantial additional costs linked to reduced electricity transmission tariffs, carbon price compensation mechanisms, and indirect financial support embedded in broader energy system subsidies remain only partially recognized. Consequently, the real public financial commitment to hydrogen is likely to far exceed the €9 billion currently projected, potentially creating an open-ended fiscal liability for the French government.

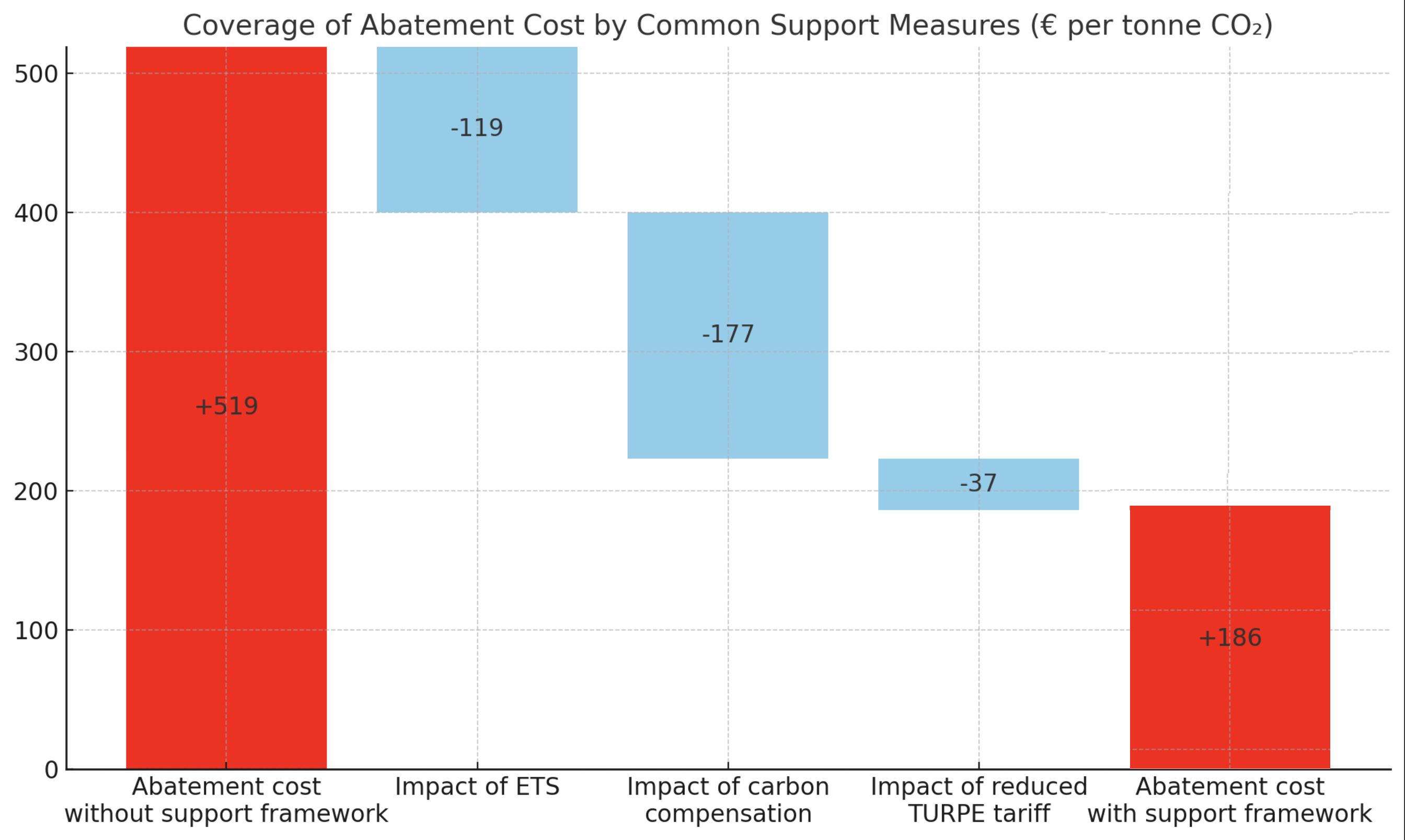

The Cour des comptes highlights a key dimension of this economic puzzle, the web of overlapping subsidies already substantially defraying the actual cost burden borne by hydrogen producers. These include the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), carbon price compensation mechanisms, and notably, reduced electricity transmission tariffs (TURPE).

In France, the ETS effectively subsidizes hydrogen by increasing the cost of carbon emissions from competing fossil-fuel-based hydrogen production, at least in the framing of the audit group. Fossil hydrogen, primarily produced via natural gas reforming, incurs significant ETS compliance costs due to its substantial CO₂ emissions. By imposing these additional carbon costs, the ETS indirectly reduces the relative price disadvantage of electrolytic hydrogen, making it somewhat more competitive.

Framing the ETS as a subsidy for electrolytic hydrogen is unusual and a criticized approach. Portraying ETS compliance costs borne by fossil-based producers as subsidies for cleaner solutions inverts the traditional logic of carbon pricing. The ETS is fundamentally designed as a “polluter pays” mechanism, placing a price on carbon emissions to reflect their environmental costs, rather than as a support system intended to subsidize alternative technologies.

Equating the avoided cost of ETS permits with a subsidy misrepresents market dynamics. A subsidy typically involves a direct financial transfer or explicit price reduction funded by public resources, whereas ETS costs represent penalties internalizing previously externalized environmental costs. By this logic, non-emitting technologies like electrolytic hydrogen simply do not incur this additional expense because they do not emit carbon, rather than actively receiving a benefit.

However, removing this still leaves a cost per ton of avoided CO2 of €400, many multiples of the costs of wind and solar generation, battery storage and electrified transportation. Even without this odd choice, green hydrogen is an expensive way to decarbonize.

Accepting the framing, however, collectively the subsidies currently cover about 75% of the €520 abatement cost. ETS market mechanisms provide an effective subsidy of roughly €119 per ton CO₂, carbon price compensation further reduces costs by €177 per ton, and lower electricity transmission fees offer an additional €37 per ton reduction. Yet, even after stacking these considerable supports, producers remain burdened with an abatement cost of approximately €186 per ton CO₂. This residue is still substantially above typical carbon prices seen internationally, underscoring how expensive and ultimately economically inefficient green hydrogen remains.

Perhaps most critically, the report challenges the logic behind allocating nearly half of France’s public hydrogen subsidies to the transportation sector, particularly road transport applications. The logic underpinning support for hydrogen in vehicles, notably passenger cars, buses, and trucks, is exceptionally tenuous given the overwhelming economic and operational advantages of battery-electric technologies. While battery-electric vehicles have established robust market momentum, declining costs, and widespread consumer acceptance, hydrogen vehicles remain persistently expensive and burdened by infrastructure complexities, fueling inefficiencies, and higher operational costs.

France’s outsized financial backing for hydrogen in transport represents a stark misallocation of scarce public resources. Public funds are effectively subsidizing an inferior technological pathway, diverting money away from far more cost-effective and proven electrification options, options which have a much lower cost to avoid CO2e emissions.

By contrast, the report points to more defensible and strategically sensible hydrogen applications, notably heavy industry sectors such as steel manufacturing, ammonia production, and refining. These industries currently rely almost entirely on fossil-derived hydrogen, generating substantial emissions and presenting genuine decarbonization challenges. Targeted hydrogen investments in such sectors offer clearer and more justified opportunities for meaningful emission reductions, given fewer viable alternatives.

Beyond simply comparing use cases, the Cour des comptes underscores a deeper fiscal and strategic risk from France’s current hydrogen approach. There are significant opportunity costs associated with disproportionately large subsidies directed at uneconomic hydrogen production and applications. Every euro directed toward inefficient hydrogen strategies is a euro not spent on expanding proven, scalable, and more economically attractive decarbonization solutions, such as renewable energy expansion, grid enhancement, battery technology, and deep electrification initiatives. The risk is compounded by potential technological and infrastructure lock-in effects, wherein continued subsidies incentivize the creation of long-lived hydrogen assets and infrastructure that may burden future public finances and constrain policy options.

France is not alone in this predicament. Similar hydrogen enthusiasm, accompanied by massive public subsidies, can be found across Europe, the UK, and the United States. Yet, France’s situation is especially instructive given the explicitness of the Cour des comptes’ warnings. Clear-eyed analyses, such as the French court’s recent report, highlight uncomfortable truths: electrolytic hydrogen at scale, with today’s cost structures and market conditions, simply does not add up economically without continuous and enormous public support.

The audit groups’ warnings follow on the joint guidance from France’s Conseil d’analyse économique and Germany’s Council of Economic Experts earlier this year, explicitly recommending that hydrogen-based road freight strategies be abandoned. These influential economic advisory bodies examined total ownership costs and concluded that battery-electric trucks decisively outperform hydrogen trucks economically and operationally. They specifically criticized continued public subsidies for hydrogen truck infrastructure, urging policymakers instead to channel resources into building out megawatt-scale electric charging along key transport corridors

Moving forward, France and indeed, any nation seriously considering hydrogen as a part of its decarbonization strategy must rationalize and refocus its hydrogen policy. Public resources should be deployed strategically, targeting sectors where hydrogen presents genuine decarbonization advantages, rather than being broadly scattered across inferior use cases. Policies must prioritize economic efficiency and technological realism, supporting applications and investments that genuinely advance both climate and economic objectives. Hydrogen’s role should be carefully limited, clearly defined, and economically justifiable, ensuring that climate ambitions align with sound fiscal and environmental responsibility.

The Cour des comptes’ report serves as a critical wake-up call. At either €400 or €520 per ton of CO₂ avoided, France’s hydrogen ambitions, unless radically recalibrated, risk becoming a costly climate misstep. The pathway to sustainable, affordable decarbonization demands greater economic rigor, transparency, and strategic coherence. France now has a clear opportunity to embrace a more pragmatic hydrogen future, one anchored not in ambitious projections and subsidies, but in a realistic acknowledgment of economic realities.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy