Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and/or follow us on Google News!

In the early 2010s, China was the promised land for American automakers. General Motors sold more vehicles there than in its home country. Buick, a brand fading into irrelevance in North America, was reborn as a prestige marque in Chinese cities. Ford had late but strong momentum, while Chrysler quietly moved metal through joint ventures. For a while, it looked like Detroit’s future was tethered to China’s rising middle class, and that America’s combustion engine muscle would fuel another golden age, just on different soil. That future didn’t materialize, but Trump 2.0’s trade war and Chinese nationalist pride did.

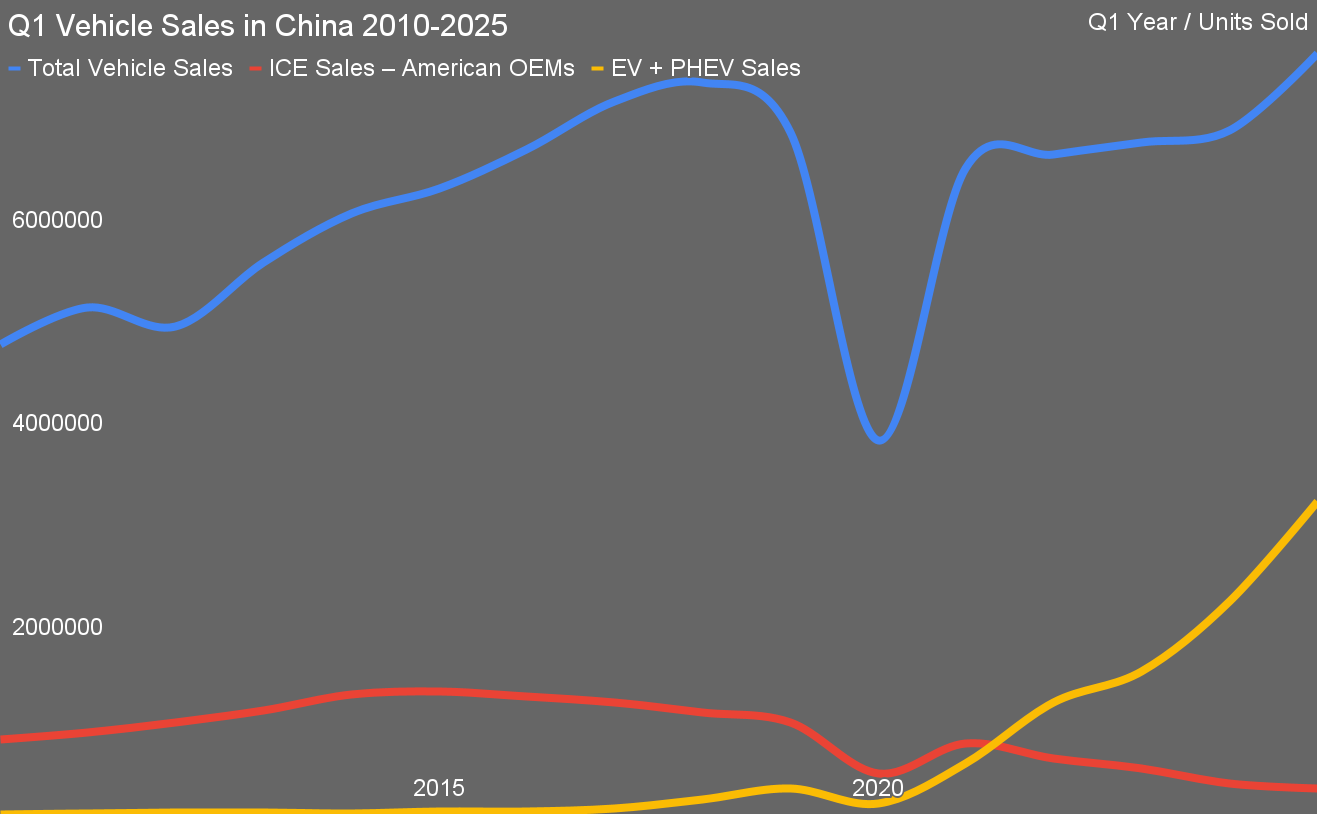

The numbers speak with a clarity few corporate strategy memos ever achieve. In Q1 2014, American-branded internal combustion vehicles sold in China in volumes approaching 1.2 million. By Q1 2025, that number had collapsed to around 250,000. This wasn’t a momentary blip or a COVID hangover. It was a structural collapse. While the total Q1 auto market in China hit new highs — over 7.4 million vehicles in early 2025 — American ICE brands lost four out of every five customers they had a decade earlier. Even as China’s appetite for cars grew, it stopped craving what America was offering.

It didn’t happen overnight. From 2015 onward, Chinese automakers began to grow more confident, more capable, and more focused on electrification. Meanwhile, American brands doubled down on their strengths: trucks, SUVs, and combustion powertrains. In China, those strengths were rapidly becoming liabilities. Between 2015 and 2020, internal combustion cars were already losing market share as NEVs, China’s term for battery-electric and plug-in hybrids, accelerated. But the real break came after 2020. Electrification wasn’t just happening, it was consolidating. Chinese brands like BYD, XPeng, and NIO took leadership in segments that used to be owned by the likes of Ford and GM. BYD in particular raced past most foreign brands in volume and margins. What had once been a question of if China could build world-class cars quickly became a question of why foreign brands were still trying to compete at all.

By Q1 2025, NEVs made up over 40% of new vehicle sales in China. That percentage is not just a statistical artifact; it represents a massive consumer pivot toward electric mobility. It also represents where the market is heading globally, because the EV transition’s pace will not be set by the laggards. It will be set by the leaders, and China is a full lap ahead. The retreat of American internal combustion offerings is a logical consequence of this shift. The Chinese consumer doesn’t want the past, and US brands showed up a decade too late to the future.

Another lens for this is Chinese consumer confidence and the robustness of the economy. While western media appears to be manufacturing yet another series of headlines about China’s imminent collapse, the data strongly suggests otherwise. As I noted recently, steel exports are up 6% in Q1 and reported GDP is tracking to 5.4% annually. The increase in car sales aligns with that data to show a growing economy. (For those interested in the 35 year history of “China is about to collapse” headlines, I recently found an old graphic of them and added a sampling of more recent ones. It’s available here. There’s always a market for this kind of nonsense, as Gordon Chang continuing to be listened to makes clear.)

The situation could be viewed through the lens of simple market adaptation — US automakers made the wrong bet and got out-innovated. But that alone doesn’t explain the velocity of decline between Q1 2024 and Q1 2025. In a single year, American-brand ICE sales in China dropped from roughly 300,000 to 250,000 units — a 17% decline in a market that grew 11%. This wasn’t just market dynamics; it was rejection. And that rejection has a political undertone. The trade war launched during the Trump administration and sustained across subsequent years didn’t just reshape tariffs. It reshaped sentiment. Chinese consumers began to question the value of American goods. More importantly, they began to feel that buying domestic was not just logical, but patriotic.

That 17% drop is more than any other nationality’s drop. Germany dropped by about 14%, which is still every significant, but Japan and South Korea dropped by only 4% and 1%. This isn’t just a rejection of ICE cars, although that’s certainly part of the equation. While mostly about Trump, it is likely also an Asian alignment.

The collapse in US vehicle imports to China reinforces this trend. By Q1 2025, only 8,870 American cars were imported into China, a 66% drop year over year. Tesla, despite its Shanghai Gigafactory, paused new orders for imported models as tariffs bit into price competitiveness. While American-branded cars manufactured locally still moved some volume, their positioning in the market grew precarious. Joint ventures once seen as entry points now looked more like quarantine zones, where outdated models lingered as Chinese competitors surged ahead with software-defined vehicles, EV-first architectures, and digital ecosystems tailored to domestic preferences.

Tesla’s story is more nuanced. It isn’t part of the American ICE decline directly — it only sells EVs — but its China trajectory is illustrative. Tesla’s Q1 2025 China sales fell to roughly 134,600 units in the domestic market, down slightly from a year earlier, even as it retained a strong export business. It’s still a major player, but the aura of inevitability is gone. Chinese brands now compete on price, performance, and technology, and win on all three. Tesla is still the best of the American auto sector in China, but even it is being slowly overtaken by the very companies it once outpaced. The writing is on the wall for the others.

Consumer nationalism is not a passing fad in China. When the government signaled discomfort with Apple’s dominance in government agencies, the market responded. Huawei phones surged back into favor. When Nike and Adidas faced controversy, domestic brands like Li-Ning and Anta gained ground. The auto sector was always going to follow this path, particularly given how closely it’s tied to economic policy, technology development, and national identity. Automakers are more than brands in China — they’re symbols of industrial strength. That GM and Ford were still offering ICE cars as their primary portfolio made them not just old-fashioned, but politically tone-deaf.

It’s worth remembering that other countries have felt this backlash. South Korean automakers were gutted in China after the THAAD missile defense spat in 2017. Hyundai and Kia lost half their market share almost overnight. Japanese brands saw similar crashes during territorial disputes. The American case has been slower, but the outcome is converging. The trust has eroded. The value proposition has evaporated. The domestic alternatives are now better and carry the advantage of national solidarity. That’s not a fight Detroit is equipped to win.

The implications extend beyond sales figures. Losing China means losing access to the most advanced EV ecosystem in the world. It means losing scale in battery supply chains, losing exposure to fast-cycle software innovation, and losing visibility into the competitive dynamics that will shape global transportation. Even if Ford or GM succeed in North America with electrification, they are playing on a smaller field. And the scale that Chinese EV makers are achieving now will enable them to price more aggressively and out-innovate more quickly in every export market from Southeast Asia to Europe. American automakers, having once used China to underwrite their global ambitions, are now watching from the sidelines as China builds the future without them.

Some will argue there’s still time. That American brands could pivot, bring competitive EVs to market, reconfigure joint ventures, and rebuild trust. But that underestimates the power of consumer perception and policy momentum. China’s EV subsidies may have tapered, but its industrial policy remains sharply focused. It has already chosen its winners, and they are mostly homegrown. The window for re-entry is not closed, but it’s narrowing fast.

The American ICE collapse in China is not an isolated market failure. It’s a bellwether for what happens when incumbents mistake momentum for immunity. It’s a case study in how geopolitics, innovation, and consumer behavior intersect. It’s also a mirror: a reflection of what happens when you try to sell yesterday’s machines in tomorrow’s marketplace. The Chinese buyer has moved on. The question now is whether the American automaker can even catch up, or whether it will just keep looking in the rearview mirror, wondering where the market went.

Personally, my bet is on US cars only having a market inside the weed-filled protectionist domestic market. That’s what’s going to happen with American-manufactured batteries, solar panels and wind turbines too. Meanwhile, every other country in the world will increase its trade with China, selling them the products they want under an increasing number of free trade deals and buying more Chinese products. The United States is isolating itself and as I noted regarding the sane-washing of the tariffs, the logic for doing so is missing.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy